Every step you take — every path you walk — exists because a young man from Suriname refused to believe that impossible meant impossible. A true forgotten genius.

His name was Jan Ernst Matzeliger.

And his story is one the world should whisper every time we tie our shoes.

The Young Immigrant Who Spoke No English

Jan Ernst Matzeliger arrived in the United States from Suriname in the late 1800s, speaking no english and knowing no one. He was a mixed-race immigrant in a deeply divided country, entering a world that didn’t see him as an equal — or even as a possibility.

But Jan didn’t care about rules.

He didn’t care about what society said was “normal.”

He was here to build something greater than permission.

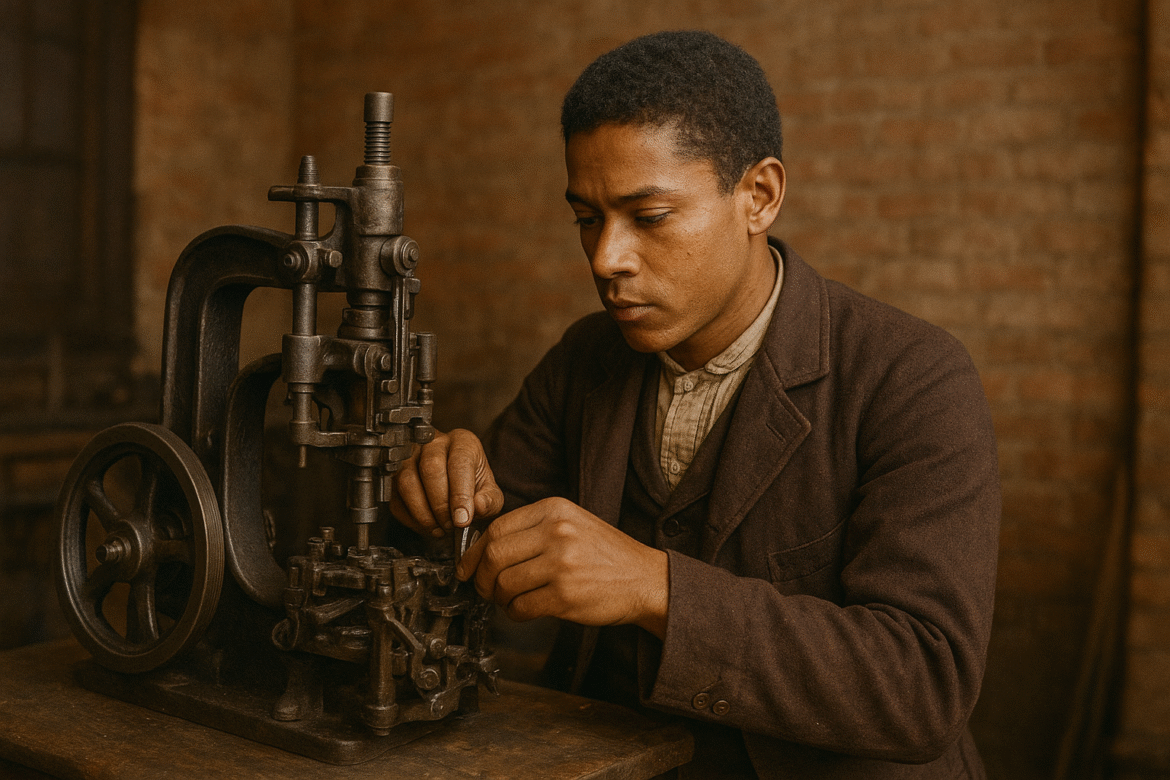

He took the brutal factory jobs no one else wanted — long hours, endless repetition, and meager pay. But when the others went home, Jan stayed up late. He studied mechanical drawing, engineering, and advanced machinery — all self-taught from books he could barely read at first.

He learned english by ear, word by word, while his hands were blistered from the machines that fed the world’s hunger for profit. He wasn’t born into privilege or connections — but he was born with something rarer : The refusal to let limitation define him.

The Impossible Problem

In the late 19th century, shoe production was mostly mechanized — except for one crucial step : Attaching the upper part of the shoe to the sole.

It required the delicate skill of expert “lasters.” But each laster could only produce a few pairs a day.

Factories believed it was impossible to automate.

They said “No machine can mimic the human touch.”

They said “Don’t waste your time.”

Jan heard the same words that stop most people : ‘It’s impossible’ ‘Stop Being Foolish’ ‘You Are So Naïve.’

But he didn’t live by the world’s rule book. He knew these defeatist words are the very ones that help identify the unwritten rules where opportunities lie.

He went home after factory shifts, sketching, carving, testing, and rebuilding.

He designed, built, and failed.

He built again — and failed again.

Investors laughed in his face. Colleagues mocked his accent. Society dismissed his race.

But Jan Ernst Matzeliger didn’t stop.

The Machine That Changed the World

In 1883, after years of relentless iteration, Matzeliger patented his creation — U.S. Patent No. 274207 — the “Lasting Machine.”

It could attach a shoe’s upper to its sole with more precision, speed, and efficiency than any human could.

Shoes that once cost several dollars to make could now be produced for mere cents.

He had done what every expert said was impossible.

He had made shoes affordable for the world — giving the poor, the working class, and the forgotten the basic dignity of good footwear.

He didn’t just change an industry.

He changed what it meant to be poor.

The Forgotten Genius

Jan Ernst Matzeliger never saw the full impact of his invention.

He died in 1889 at the age of 36 — young, poor, and largely forgotten.

But his legacy never stopped walking.

Every worker, every child, every person who’s ever owned a pair of shoes — owes a step to Jan.

His name should be as famous as Edison, as celebrated as Ford, as known as Bell.

But it isn’t.

Not yet.

And that’s exactly why NoRuleBook exists — to remind the world that greatness doesn’t follow rules, privilege, or permission.

It follows belief, grit, and defiance.

Lessons We Can Learn from Jan Ernst Matzeliger

1. You don’t need permission to change the world.

Jan didn’t wait for acceptance. He created his own opportunity in a world that refused to see him.

2. Education isn’t what you’re given — it’s what you take.

He taught himself English, engineering, and design — all from scratch. The only school he needed was his own hunger to learn.

3. Failure is just the raw material of invention.

Jan’s brilliance was built on repeated failure. Each setback wasn’t an ending — it was a recalibration.

4. The impossible is often just unexplored territory.

Every “no” he heard became proof that no one else had tried hard enough.

5. Legacy isn’t about fame — it’s about impact.

He died unknown, but his invention lives on in every step humanity takes. That’s immortality of the truest kind.

Jan Ernst Matzeliger lived a NoRuleBook life.

He refused to accept the labels society gave him — immigrant, outsider, poor, uneducated.

Instead, he wrote his own rules, with his own hands, and built a machine that reshaped the world.

So the next time you lace up your shoes, remember:

You’re walking in the footsteps of a man who never followed the rule book – Because he was too busy writing his own.